July 27, 2020

July 27, 2020

Hold Security’s Dark Web Monitoring Services uncover private details about the YouTube Cryptocurrency Ad Scammers.

Months before Twitter was hit with a modern version of the “Nigerian prince giving away his fortune” bitcoin scheme, there were several groups on the Dark Web engaged in similar scams on YouTube. Cybercriminals from India teamed up with counterparts from Kazakhstan and the Philippines to abuse social media, spreading misleading videos featuring famous individuals and asking to send Bitcoins or Ethereum cryptocurrencies in order to “double” your investments.

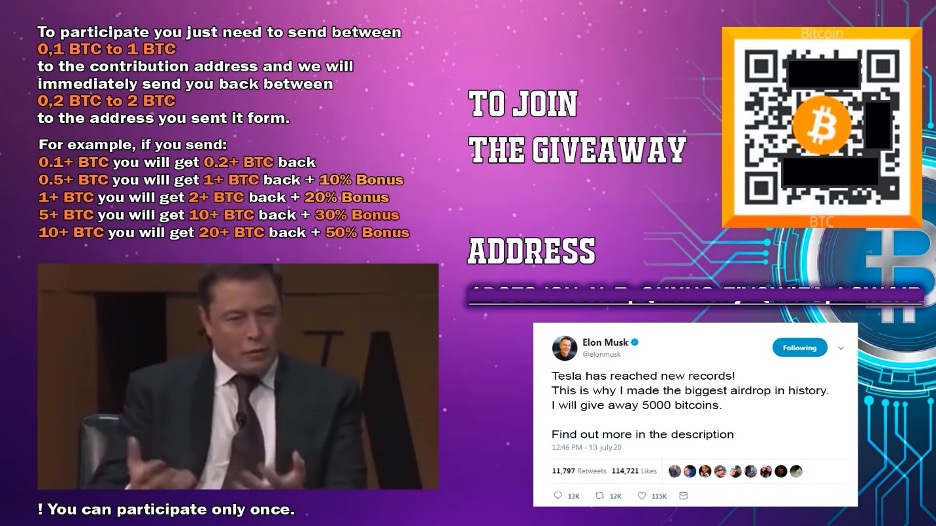

Amongst the celebrities impersonated you will find Jack Dorsey, Mark Zuckerberg, Steve Wozniak, Larry Ellison, Kevin O’Leary, Kylie Jenner, John McAfee, and Joe Rogan. Also impersonated are several cryptocurrency gurus like Changpeng Zhao (CEO of Binance) and Vitalik Buterin (Ethereum Founder) whose likeness is used in videos to build legitimacy to the scam. Videos are posted on YouTube from realistically named accounts and they are advertised via several marketing ploys. The videos usually feature a real interview with a famous person as a focal part of the screen with the rest of the screen occupied by offers to send a cryptocurrency to an address in order to double your money. A week before the Twitter breach, in an eerie foresight of what is yet come, here is a screenshot from one of the videos posted on YouTube with a fictional tweet from Elon Musk about a bitcoin giveaway.

All this activity is not going unnoticed. Recently, Steve Wozniak and 17 other victims filed a lawsuit against YouTube/Google’s parent company Alphabet Inc. for this (and/or similar) activity not being properly contained. Unsurprisingly, a quick search in the gang’s documentation shows several videos featuring Mr. Wozniak taken down but a few still unflagged:

https://telegra.ph/Steve-Wozniak-announces-5000-BTC-Giveaway-COVID-19-06-04

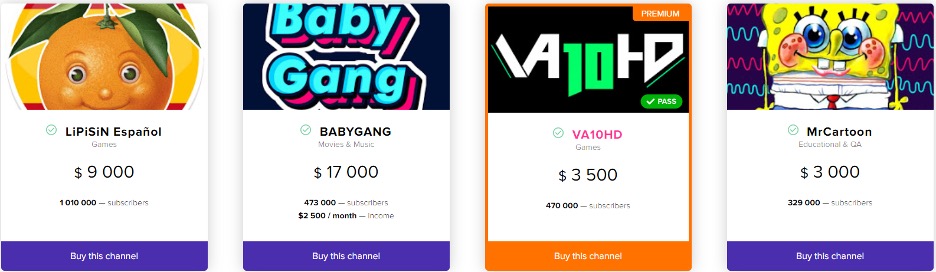

The criminals work in several directions. One of the main issues is to build a video that will pass YouTube’s anti-spam filters. Dozens of versions of the same video may be generated and all of them will be tested for scam detection. Also, the cybercriminals are watching the news, Twitter feed, and other sources to see if anyone detected their scheme so they can switch them for undetected ones. How to get the audience is an equally important task. The bad guys go to the Dark Web looking for YouTube channels to buy. They frequent one site where you can buy channels with audiences of hundreds of thousands:

Since they operate hundreds of YouTube accounts and claim that they can create at least a hundred more each day, the gang uses them to leave positive comments under each video to build more legitimacy.

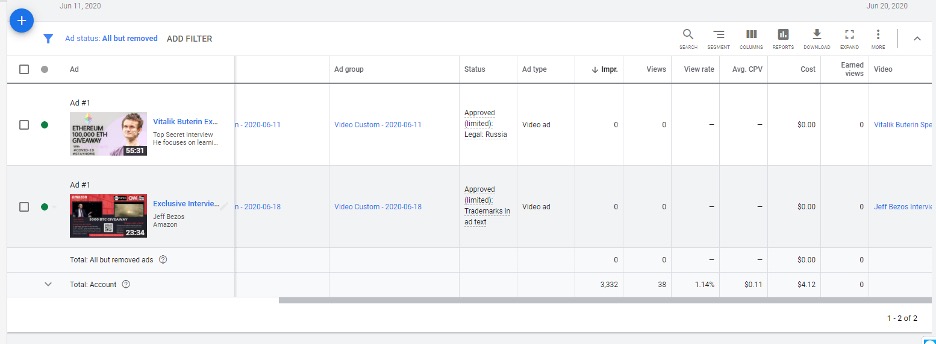

They also spend money to advertise their links. Using various advertising platforms, they build complex advertising campaigns for each video measuring carefully successes and failures.

Through a myriad of proxies, rented or stolen systems, fake accounts, and fake websites which are also used to promote the scam, the gang is driving large amounts of traffic to their malicious videos.

Even though the team is not big, there is a large amount of accounting documents that we were able to review to gain a better understanding of their criminal activity. For example, advertising spreadsheets detail not only URLs of malicious videos, but the entire process of abuse tediously mapped out and benchmarked.

Very meticulous financial details including marketing expenses, transactional fees, and the ill gains are mapped. The crime cycle is not cheap with their accounting records showing expenses associated with marketing, stolen system purchases, payoffs to other team members, and other expenses amassing to more than 50% of the profits. Yet, the crime pays tens of thousands of dollars collected so far.

Other data like online storage repositories with images, videos, and editing material consist of gigabytes of data as the gang is trying to pick the right formula with the biggest impact.

Based on gang’s careless use of Google Docs components, we obtained data about several individuals in the gang:

The group leader, Satvik G, referred by his group as “Mr. Satvik” is not a stranger to cybercrime. With a long track of abuse of social media, he first propagated fake ads on Facebook before moving to YouTube abuse in search of higher profits. He does not see himself as a cybercriminal though, in his eyes he is a marketing entrepreneur not trying to hide his identity from anyone who would look deeper. His gang is not being recruited on the Dark Web but through freelancer sites to find hard working individuals who see their activities as a real job.

The hiring process is simple, job negotiations are real, and recruits are coming from all parts of the world. Using freelancer site Upwork, Mr. Satvik recruited several women from the Philippines whose job is to add technical data (i.e. browser cookies) into software used for automatic postings and to keep track of various tasks. Paying only $1.25 per hour, $10 for a full workday, he demands attention to detail, minimal (unpaid) breaks, and loyalty to his efforts.

While his group generates hundreds of fake accounts, numerous videos, and fake landing sites, it operates like a real business. Profit and Lost statements are posted for each month and all successes and failures are neatly listed using Google technology with the same company that they are abusing in their scam.

The Twitter breach did not phase them. While the breach was on-going, they were exchanging data and planning another abuse video. Yet, the lessons from this breach did not pass them by. They felt that their plan was working and after July 15th they simply chose to step up their game.